|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Click here to Download PDF |

PROPOSING THE OPERATIONALIZATION OF THE ART. 125 SOLUTION: ESTABLISHING THE NINEVEH PLAIN ADMINISTRATIVE UNIT |

| |

Iraq Sustainable Democracy Project POLICY BRIEFING

October 2007 (Updated February 2008) |

| |

| 1. Introduction |

On October 22nd and 23rd of 2003, a gathering took place in Baghdad of Iraq’s vulnerable, indigenous Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac people. That unprecedented gathering, both in numbers and the leadership roles of attendees, allowed the Assyrian Democratic Movement (ADM) to declare the following with total confidence: “The Conference stressed the need to designate an administrative region for our people in the Nineveh Plain with the participation of other ethnic and religious groups, where a special law will be established for self-administration and the assurance of administrative, political, cultural rights in towns and villages throughout Iraq where our people reside.”

Since that time, a great many ChaldoAssyrian politicians and political entities have adopted and endorsed the vision set forth in that declaration. These include small parties represented in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), such as the Assyrian Patriotic Party, ChaldoAshur Organization of the Kurdistani Communist Party, the Chaldean Democratic Forum, the Chaldean Cultural Association of Ainkawa, and the Bet-Nahrain Democratic Party.

More importantly, the highest profile ChaldoAssyrian within the Kurdistan Regional Government, Finance Minister Sarkis Agha Jan, has also adopted the policy set forth in the ADM Declaration of 2003. He formally articulated this position in a Guardian News interview, which reported, “[Aghajan] … is convinced that the only way to secure protection in the longer term is for an autonomous region, a safe haven, to be established covering Nineveh’s Christians, as well as smaller communities there such as the Yezidis and the Shabak. ‘This special region would help us to maintain Christian history in that place. In that way there would be no way for Kurds or Arabs to intervene. This would encourage the Christians living outside to come back and it would be an example to the Middle East.’”

With respect to the political action plan and determination to see the realization of territorial federal rights for ChaldoAssyrians, Iraqi news sources are still profiling the continuing, focused role of the ADM in the matter. The Kurdish Aspect recently reported the following from its interview with ADM representatives that are parliamentarians in the Kurdistan Regional Government legislature:

“Galawizh Shaba Jarjeez, a member of the Kurdistan Parliament, believes that the draft Kurdish Constitution denies her people their rights. Jarjeez, a member of the Central Committee of the Assyrian Democratic Movement, sent a memorandum to parliament and to the committee that is responsible for the draft Constitution, outlining their demands. […] The draft Constitution states that Telkef, Qaraqosh and Baashiqa are part of the Kurdish region whereas Jarjeez and her counterparts say that they are part of the [Nineveh] Plain and should be treated as a special autonomous region. It is special, they say, due to its multinational and religious nature and that under Art. 125 of the new Iraqi Constitution, they should be allowed to achieve these rights.”

The articulation of the political will and aspiration to form a federal unit under Art. 125 is clear. The urgency for operationalizing the Art. 125 solution is undeniable when combined with the very real fact that ChaldoAssyrians are being wiped out of Iraq. The Nineveh Plain Administrative Unit policy is necessary to avert their total cleansing from their indigenous homeland. The following policy briefing on the matter arises from solicitation of ISDP to set forth a vision for how this plan is constitutional, politically feasible and necessary for achieving US strategic goals in Iraq.

|

| 2. Guiding Constitutional Principles |

In accordance with Art. 125 of the Constitution of Iraq, this proposal puts forth the framework for formalizing the existence of the Nineveh Plain Administrative Unit (NPAU). Art. 125 of the Constitution states, “This constitution guarantees the administrative (in Arabic, ‘al-Hoqooq al-Idaariya’), political, cultural, and educational rights for various ethnicities such as Turkmens, Chaldeans, Assyrians and the other components, and this shall be regulated by law.”

Although Art.125 does not explicitly name Yezidis and Shabaks, they too form a critical element of the social and political fabric of the Nineveh Plain. The formalization of the Nineveh Plain as an administrative unit demonstrates Iraq’s commitment to enshrining the rights of some of its most vulnerable minorities within a framework of territorial federalism. Indeed, it would be the exemplar for showing Iraq’s inclusiveness and intent to fully realize the potential of the constitution for the good of all Iraqis. Formalizing the Nineveh Plain is also the most efficient and effective means of fulfilling Art.125 given the contiguousness of the territory and its existing governing institutions and long history. It is the least disruptive measure for ensuring the realization of the rights stipulated in the constitution to these peoples.

The Nineveh Plain is comprised principally of minorities. For over six millennia, the Assyrians have made the Nineveh Plain their home – being the indigenous people of Iraq. Much of their contribution to human civilization as sons of Mesopotamia is found in their lands on the Nineveh Plain. Yezidis and Shabaks, over time, have come to become a vital element of the Nineveh Plain, contributing robustly to its rich history. They also have significant populations in the region, along with smaller Turkmen, Kurdish and Arab peoples; all of whom have a rich history in the area. This is a uniquely heterogeneous entity. The intent is, by actualizing Art.125, to allow these minorities to make their fullest contribution to the growth of a strong, democratic and pluralistic society in Iraq.

Currently, the NPAU policy is taking on a level of urgency heretofore unseen as a result of the ethno-religious cleansing taking place of Iraq’s ChaldoAssyrian Christians. Upwards of 1 in 3 is now a refugee in neighboring Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, among other locations. An even greater percentage is internally-displaced and facing conditions driving them completely out of the country. The annihilation of this minority is a development being looked on by other similarly vulnerable minorities with grave concern. It is for this reason that Art. 125 and the NPAU policy is being driven as a solution for the good of Iraq in the long-term and something to ensure Iraq remains ethnically and religiously plural in the short-term.

Art. 116, which states, “The federal system in the Republic of Iraq is made up of a decentralized capitol, regions, and governorates, and local administrations.” is the main provision establishing Iraq as a federation, and enshrining federalism as a defining feature of its political landscape.

Policy-makers will note that Art. 125 is the only article of the Constitution for the chapter on ‘local administrations’, and states, “This Constitution shall guarantee the administrative, political, cultural and educational rights of the various nationalities, such as, Turkomen, Chaldeans, Assyrians, and all other constituents, and this shall be regulated by law.”

Dr. Yash Ghai, the internationally renowned constitutional expert assigned specifically to work with Sheikh Hamoudi, Chairman of the constitution drafting committee, writes this about Art. 116, “The fifth section (‘Powers of Regions’) deals with the powers of regions and governorates (in addition to those in section four). It has four chapters, respectively on regions, governorates not incorporated into a region, the capitol and local administrations (the last of which is concerned not with local governments but protection for minorities).” It must be re-emphasized that this provision is deliberately placed within the section on federalism.

Effectively, what experts are saying, including Dr. Yash Ghai, is that ‘Local Administrations’ is in fact far removed from recognizing local government, or local level administrative bodies standardized throughout the country.

What is being identified are exceptional federal units that are meant to secure protective measures that guarantee Iraq’s minorities can make a constructive contribution to Iraq’s stability and development through federal arrangements that are territorial. There are several other instances where the Constitution of Iraq reinforces this understanding.

To further emphasize the fact that ‘local administration’ (in Arabic, ‘idaraat mahaliya’) has little to do with local government, analysts note that Art. 93 on the jurisdiction of the Federal Supreme Court, sub-section (4), states the Federal Supreme Court shall settle, “disputes that arise between the federal government and the governments of the regions and governorates, municipalities, and local administrations.” In this case, “municipalities (as local government in the classic sense, in Arabic, ‘al-baladiyaat’) are distinctly separated from “Local Administrations” . This deliberate separation of municipalities from Local Administrations seeks to establish the latter as stand alone, unique federal units within Iraq’s burgeoning federal system.

Also recall that Art. 122(1) states, “The governorates shall be made up of a number of districts, sub-districts and villages.” In this case, the Constitution is clearly articulating that governorates are made of sub-units separate from “Local Administrations”, otherwise the specific term ‘Local Administrations’ would have been employed in the article.

To be clear, Art. 116 identifies “a decentralized capitol, regions, and governorates, and local administrations” as the principle territorial units of a federal Iraq. It is also clear that the Constitution of Iraq distinguishes between local government/municipalities, districts and sub-districts by dedicating the only constitutional article on “Local Administrations” solely to the enshrinement of an array of rights for vulnerable minorities, especially the indigenous ChaldoAssyrians.

The framework for proposing the formalization of the NPAU also recognizes the present legal status of the area in relation to the provinces of Ninawa and Dohuk (the latter is situated in the Kurdistan Region). Art.116 states, “The federal system of the republic of Iraq is made up of the capital, regions, decentralized provinces and local administrations.” Additionally, Art.122(1) states that, “Provinces consist of districts, counties and villages.” It is acknowledged that the Nineveh Plain is located across two existing provinces. Art.125, however, indicates that certain minorities (ethnic and religious) require exceptional arrangements to fully and equitably realize their rights in a federal Iraq – separate from having representation in districts, counties and villages where they have significant populations.

It will therefore be necessary to seek language in the Kurdistan Region’s Constitution on arrangements to provide a linkage between that part of the NPAU situated outside of the KRG and that which lies in Dohuk. Nonetheless, this issue in no way prevents the essential and feasible pursuit of establishing that part of the NPAU lying south of the KRG as an Art. 125 federal unit while also seeking to develop the legislation required to one day merge it with the territory of the unit that would overlap with the KRG.

As per Art. 4(4) of the Constitution, the official languages of the NPAU will be Syriac/Aramaic, Shabak, Arabic and the Turkmen language.

The approval and subsequent formalization of the NPAU does not preclude further redefinition of its legal status (territory, powers/functions and authority) in future legislation on federalism. Any redefinition cannot roll-back the legal status achieved through the formalization of the NPAU. It may only increase its jurisdictions (with respect to powers/functions and territory).

|

| 3. Powers of the Nineveh Plain Administrative Unit |

The powers of the Nineveh Plain and framework for inter-governmental relations between the NPAU, the Province and the Federal Government in Baghdad are guided by the principle of administrative decentralization. This is put forth in Art.122(2), which states that, “Governorates that are not incorporated in a region shall be granted broad administrative and financial authorities to enable them to manage their affairs in accordance with the principle of decentralized administration, and this shall be regulated by law.” The principle of administrative decentralization seeks to maximize the economy, efficiency and effectiveness of the state in its arrangement of authority through the devolution of powers to the most appropriate levels of government.

The constitutional principle of decentralized administration logically extends to “local administrations” such as the NPAU by virtue of its identification in the list of federal units specified under Art. 116.

The following division of powers recognizes that the NPAU is the primary, front line governmental delivery agent for most basic goods and services, and is most directly connected to the population. Taken with the impetus to form an administrative unit as per Art.125 of the Constitution, the need for robust powers to ensure delivery of government goods and services is self-evident.

|

| 3.1 Nineveh Plain Administrative Unit Specific Powers |

Most important are the powers of the NPAU. It would be responsible for health (pharmacies, primary health care centers, district-level hospitals,); primary, secondary and tertiary education, as well as special cultural, technical and vocational education programs; various judicial matters; economic development planning (rural and urban); social welfare; agriculture; sanitation; local policing; along with special powers regarding archeology and tourism, among others. It would have the power to tax based on its functions and therefore would also have treasury and revenue agencies. |

| 4. Fiscal Federal Arrangements |

Administrative decentralization requires that funds follow the functions devolved to each authority. The NPAU will receive funds from direct federal and direct provincial transfers on a proportional and equitable basis with other authorities to fulfill the shared and specific powers listed above. This will be provided in the budget cycle of the nation. The division of revenue will take place as defined by the law and the general body mandated to “monitor and allocate federal incomes” as per Art.106 of the Constitution.

The fair division of revenue is also consistent with the principle of administrative decentralization, as reflected in Art.122(2) which gives provinces “broad … financial authorities”. This is repeated in Art.122(5) which states that the, “Governorate Council shall not be subject to the control or supervision of any ministry or any institution not linked to a ministry. The Governorate Council shall have independent finances.”

Consistent with the principle of financial independence, the NPAU will also have the power to levy local taxes on its citizens in a manner consistent with its revenue needs given its functions and the tax system of the nation. This is in addition to the transfers it receives from federal and provincial authorities in the division of revenue process.

In the establishment of the commission responsible for the final formulaic agreements on an equitable division of revenue, there should be a variable for the NPAU in its equitable share that provides funding for redress of the persecution, suffering, ethnic and sectarian cleansing, and cultural genocide suffered by ChaldoAssyrians. The last item is reflected by the Ba’athist policy during the census that made it illegal to identify oneself as an ethnic Assyrian; allowing only for Arab and Kurdish Christians. This is just one high-profile example of the cultural genocide endured by ChaldoAssyrians to which Kurdish and Arab populations were exempt. As a result, the exceptional form of persecution, in addition to the crimes suffered by others, merits particular treatment in the division of revenue so that the NPAU and other entities can facilitate redress of the situation.

|

| 5. Representative Arrangement |

The NPAU will have an elected Governing Authority and also an elected council. There would also be district and sub-district elected officials to manage purely local affairs, along with town and village mayors and councils. This would be just as is done for any federal unit.

The NPAU would also be directly linked to the federal government. In this way, the Governing Authority of the NPAU would be able to vote on all federalism decisions arising from National, Regional and Governorate negotiations through institutions of inter-governmental relations.

Nineveh Plain Governing Authority departments and agencies will be developed consistent with the shared and specific powers stipulated above – while striving to attain the highest degree of economy, efficiency and effectiveness in the formation of institutions.

|

| 6. Territorial Boundary/Jurisdiction of the Nineveh Plain Administrative Unit |

|

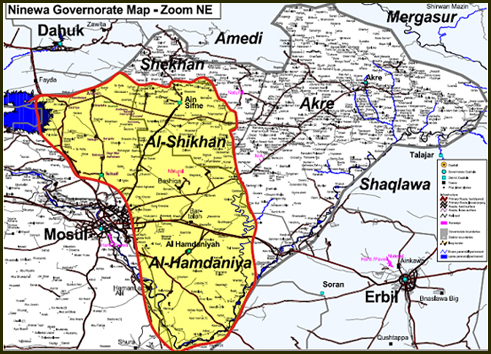

The Nineveh Plain boundaries for that part of the NPAU located within

the existing Governorate of Ninawa. |

| |

|

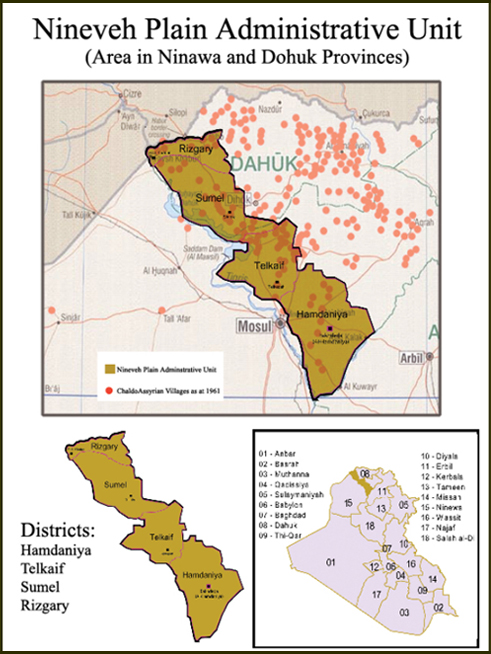

| The total territory of the NPAU overlaps with the western part of Dohuk Governorate. |

| 7. The Political Path of the Art. 125/NPAU Solution |

This final section seeks to identify the political variables that cannot be ignored in considering the ‘Art. 125 Solution’ while at the same time discussing pragmatic steps forward that assist in operationalizing this policy constructively.

It is vital to deal with the most significant concern in broaching the subject of the NPAU – ethnicity and the perceived atomizing of Iraq. The NPAU policy is often construed as an ethnically exclusive enterprise, both by ChaldoAssyrians and non-ChaldoAssyrian opponents of the plan. This cannot be further from the truth, and is clearly evidenced by the call of leaders across Shabak, Yezidis, Turkmen ethnicities. Quite contrary to the characterization, this endeavor has always been fully ethnically and religiously heterogeneous. In stark contrast to most political developments in Iraq, the NPAU is a model for transcending ethnic and sectarian lines, seen from the onset when the ADM’s own conference call identified that other ethnic groups were part of this plan.

If there is a primary threat to the future structural integrity of Iraq vis-à-vis constitutional and federal frameworks, it lies within the reality that most governorates cannot ignore the constitutional incentive to form a region. Given present trends, this will bring about a three-state partitioning of Iraq along ethnic/sectarian lines and the total collapse of security and stability that is widely feared. International experts agree that whether one examines Nigeria, Czechoslovakia, Pakistan/Bangladesh, Ethiopia/Eritrea or Yugoslavia, the common denominator of instability and/or violence is a federation with a small number of units.

By pursuing the NPAU through the operationalization of the ‘Art. 125 Solution’, a movement will begin that takes Iraq away from the destructive and politically debilitating process of pitting large stakeholders in a zero-sum calculation where potential secession provides an effective veto in political bargaining, to one where no one unit can dominate so absolutely. The creation of ‘Local Administrations’, starting with the NPAU, will signal the movement towards the actual intention and utility of federal arrangements by negating zero-sum calculations centered on ethnic and sectarian differences.

This will have positive repercussions for discussions about governorates, the formation of future regions and most importantly, the types of deliberations taking place in those institutions facilitating inter-governmental relations. By having a multi-ethnic, multi-sectarian NPAU participate in debates on national division of revenue, on the devolution of powers and other facets of federal arrangements, a guaranteed voice of reason and moderation would be created whereby national unity and progress remains the highest priority.

Put most directly, implementing the NPAU policy will precipitate the formation of other federal units that go beyond the three-state partitioning of Iraq. This reduces the ability of a few large units to consider separation. It will also mark the formal process of establishing federal units where no one ethnic or sectarian group can be highlighted as being hegemonic and allow others to pursue a similar model.

For this reason it is paramount to stop all efforts by KRG authorities to absorb the Nineveh Plain into the Kurdistan Region; an objective clearly stated in Art. 2(1) of the KRG’s Constitution.

However, it is the ADM, among others, who have formally maintained this right without connecting it to the politically destabilizing agenda of secessionism by the dominant KRG political parties.

Ultimately, and for the reasons outlined above, this is not the atomizing of Iraq federally, but the utilization of federalism, minority rights, pluralism, human rights and democracy to establish one type of federal unit that is truly heterogeneous and intrinsically interested in the unity and success of Iraq as a nation-state.

The argument thus far serves to give effect to a fundamental premise articulated in Art. 109 of the Constitution, which states, “The federal authorities shall preserve the unity, integrity, independence, and sovereignty of Iraq and its federal democratic system.” Outcomes entirely contrary to this principle are being reinforced so long as there is no recognition that the present trajectory of federalism is in fact the formation of three large ethnic/sectarian blocks, with one (the KRG) quite deliberately seeking the measures needed for eventual secession.

The Art. 125 Solution/NPAU policy is a primary policy vehicle for reversing the destructive effects evidenced to date.

The first part of the process to operationalizing the NPAU is dialogue with ChaldoAssyrian, Shabak, Yezidis and other stakeholders advocating the ‘Art. 125 Solution’. The United States Government will then be able to confirm the widespread support for the policy and concurrently discuss matters of roll-out and strategy in Iraq. In the appendix, an ISDP ‘Policy Alert’ reflects awareness of this issue by senior US Government officials in Iraq and senior elected representatives (see appendix). This is a modest start, but reflects the potential, particularly since Ambassador Ryan Crocker confirms the ability to form “a separate administrative region through processes consistent with [Art. 125].”

These discussions should take place in the United States, where these vulnerable minorities can speak more freely – many are simply ‘hostages’ to the threat of force/intimidation and assassination at this moment in Iraq.

|

| These discussions will provide for the following items: |

- Reviews of the draft Iraqi legislation required for the operationalization of Art. 125;

- Agreement on timetables for action steps by the minority party representatives (e.g. window for tabling the legislation);

- United States diplomatic weight in seeking to advance the Art. 125 Solution in Iraq through its allies and those susceptible to its influence;

- Agreement on US policies necessary for removing present obstacles to the pursuit of the Art. 125 Solution;

- Adoption of a reconstruction and development plan for the Nineveh Plain which has been almost entirely neglected in US Government reconstruction of Iraq;

- Assistance in the creation of a formal, legitimate and representative Nineveh Plain local policing force, which is presently being denied by the KDP;

- Any other United States Government policies and/or legislative measures needed to encourage and reinforce the realization of the Art. 125 Solution;

5. Agreement on US policies necessary for removing present obstacles to the pursuit of the Art. 125 Solution;

|

| |

|

The Article 125 Solution Reaffirmed by

US Ambassador Ryan Crocker |

The relative exclusion of Iraqi minorities as part of the federalism equation by Washington DC decision-makers feeds into a vicious spiral reinforcing the impression that the opportunity either does not exist, or is not seriously being considered and proposed by these minorities. Ambassador Ryan Crocker and Senator Joseph Biden recently made a significant contribution to people’s understanding of this issue.

Senator Biden, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee put forth that, “Some Iraqi parliamentarians have called for the creation of an autonomous region in the Nineveh Plains, home to a disproportionate number of Iraqi minorities, including, Assyrians, Turkmen and Yezidis.” In Amb. Crocker’s response, he confirms that, “Some Iraqi parliamentarians and local politicians in Ninawa have called for an autonomous region in Ninawa province, citing Article 125 of the Iraqi Constitution. Iraqi citizens can pursue the creation of a separate administrative region through processes consistent with this article.”

Federalism debates in Iraq are difficult. Concepts such as ‘autonomy’ take on whole new dimensions, from being a mere technical term reflecting decentralization and devolution, to becoming a banner for secessionism. Federalism is immediately understood to be partitioning Iraq, with the subsequent regional instability and violence that will follow. Minorities face insurmountable challenges in entering the federalism dialogue for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is the reality that they lack power and the credible threat of force, relying instead on the development and respect for the rule of law to achieve their constitutional rights.

In this environment, minorities managed to sustain their political goal of sharing in the benefits of federalism for stabilizing and democratizing Iraq by having Article 125 adopted in the present Constitution. That article states that, “This Constitution shall guarantee the administrative, political, cultural, and educational rights of the various nationalities, such as Turkomen, Chaldeans, Assyrians, and all other constituents, and this shall be regulated by law.” This language originates from the Transitional Administrative Law’s Art. 53(d).

Ambassador Crocker’s response to questions on federalism and minorities from hearings on the situation in Iraq where he testified alongside General David Patraeus is helpful. There is confirmation for many that Iraqi parliamentarians are actively seeking the goal of establishing some form of unique federal unit in the Nineveh Plain, as per Art. 125, and that Art. 125 is the appropriate mechanism by which to achieve this objective. The doubts of US analysts and members of minority communities should be dismissed on both matters.

ISDP’s policy briefs and reports provide extensive analysis and information on the issues around federalism and minorities. At this point in time, there is a particular focus on the Nineveh Plain as a pillar in this agenda for bringing about a truly democratic and pluralistic Iraq, where minorities can live securely and remain productive elements of Iraqi society.

The question remains, will US decision-makers recognize the importance of working to provide persecuted minorities the political space and protection they require to advance this essential agenda. For the Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac Christians, this policy is now a matter of ensuring their survival. While remaining a powerful tool for making Iraq a fully federal country with the stabilization this provides, the ‘Nineveh Plain/Art. 125 Solution’ has become a matter of urgency for a minority that is now the victim of widespread ethno-religious cleansing.

|

| |

| Click here to Download PDF |

|